ISLAMABAD, August 27, 2020: Lack of pricelist enforcement was evident in both the absence of the official list and overpricing trends observed in market monitoring survey of 36 districts across Pakistan. Traders disregarded the official prices of pulses in around two-third of the surveyed districts, meat in more than half of the regions, and other essential commodities such as wheat, sugar, and dairy in about one-third of the areas last week.

These findings form part of the 17th Weekly Price Monitor issued by the Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN), which also found that these commodities’ official prices, especially cooking oil, and tea, were unavailable in most of the surveyed markets.

The weekly monitor comprises a market survey of the prices of 15 basic groceries conducted on Thursday, August 20, 2020, in 36 cities—13 in Punjab, 12 in Balochistan, six in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and five in Sindh.

The officially notified price lists of essential commodities were unavailable in various parts of the country during the reporting week. The official rates of 20-kilogram wheat flour bags were not available in half (50 percent) of the surveyed cities. The unavailability of official wheat flour rates at shops was most significant in Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where 100 percent and 67 percent of the districts lacked the official prices.

Official sugar prices were missing in 47 percent districts—100 percent in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 42 percent in Balochistan, 38 percent in Punjab, 20 percent in Sindh. Similarly, chicken prices were not obtainable in 28 percent of the regions overall—100 percent in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 25 percent in Balochistan, and 20 percent in Sindh.

The official rates of four pulses—moong, masoor, mash, and chana—were generally available in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, and Sindh. However, more than half of the markets in the surveyed cities of Balochistan did not display the official prices of mash and masoor, while 33 percent did not display daal chana prices and 17 percent daal moong rates. At the same time, milk and yogurt rates were not publicly obtainable in 19 percent and 25 percent areas.

Moreover, mutton and beef prices were missing in 11 percent and eight percent of the districts, respectively. Provincially, beef prices were missing in 20 percent of Sindh’s regions, 17 percent in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and 8 percent in Punjab and mutton prices were unavailable in 33 percent of the markets of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 20 percent in Sindh, and eight percent in Punjab. However, all of the surveyed Balochistan markets had prominently displayed the meat prices. The official price lists of regular vegetables—potatoes, onions, and tomatoes—were inaccessible in around 17 percent to 25 percent of Balochistan markets while elsewhere they were publicly available.

The lax enforcement of official prices burdened ordinary citizens as traders sold several commodities at higher rates than the officially notified prices. The trend, as detailed below, reflects overpricing in all major food categories.

A two-week comparison of dairy’s market-prices showed overall stable patterns. Around 88 percent of the surveyed markets recorded stability in rates during the reporting week compared to the previous one. Another nine percent showed an increase, and the remaining three percent reported a decrease in prices.

The market rates of eggs per dozen were above the officially notified prices in 33 percent districts. At the same time, the rates of milk and yogurt were higher than the official ones in 47 percent and 44 percent of the surveyed areas. The prices of eggs dropped across 16 districts with the drop in prices ranging from Rs2 to Rs60 while the rates remained stable in 13 areas.

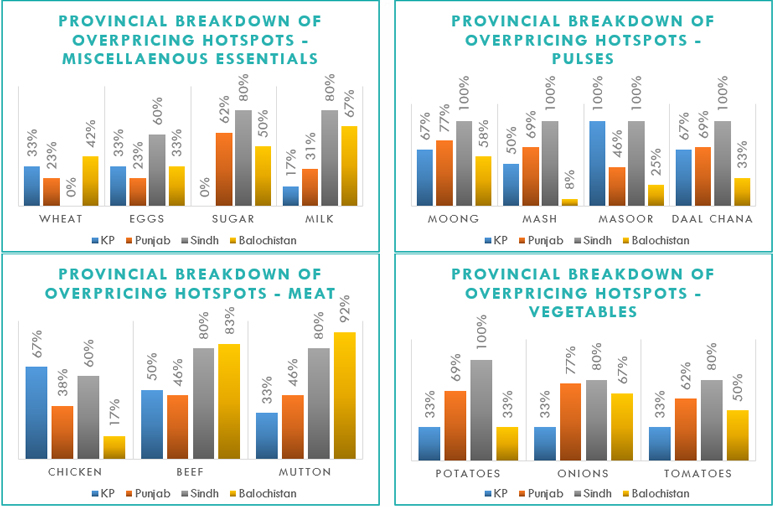

Traders sold wheat flour and refined sugar above the official rates in 28 percent and 50 percent regions. A 20-kilogram bag of wheat flour was priced Rs400 above the official rate in Washuk, and one kilogram of refined sugar was Rs36 more than the market price in Malir, Karachi. Wheat price enforcement was the weakest in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where 42 percent and 33 percent of the markets sold it above the officially notified rates. Sugar price enforcement was the lowest in Sindh, where around 80 percent of the markets sold it above the official prices. Punjab was followed by Sindh (62 percent), and Balochistan (50 percent) in lax enforcement of sugar prices. However, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa markets wholly followed the official rates of sugar.

The tomatoes’ market price showed an increase in 13 districts, a decrease in ten regions, and stability in nine areas. The highest increase per kilogram price was in Lodhran, where it jumped from Rs40 to Rs60. Upper Dir saw a decrease of Rs5, the rate falling from Rs44 to Rs39.

Similarly, potato prices registered an increase in 11 districts, decreased in nine regions, and showed stability in 13 areas. The highest uptick was Rs20 recorded in Malakand, and the most prominent drop was also of Rs20 reported from Peshawar and Rahim Yar Khan.

Onion prices registered an increase in four districts, a decrease in 11, and remained stable in 18 regions. The most significant hike was Rs20, jumping from Rs30 to Rs50, in Jafarabad, while Nasirabad saw a decrease of Rs30, down from Rs80 to Rs50.

Potatoes, onions, and tomatoes were overpriced in 56 percent, 67 percent, and 56 percent of the districts. The rate of tomatoes went Rs70 higher than the notified price in Karachi South, Jhal Magsi, and Lasbela while potatoes and onions were sold Rs30 above the announced prices in Panjgur.

Overpricing of pulses was also observed in over two-thirds of the markets surveyed. A comparative reading reflects Sindh having almost all its markets selling the four primary pulses, i.e. Moong, Mash, Masoor and Daal Chana over official prices.

The survey reflected Balochistan as the province with the least number of districts where pulses were sold over the officially notified prices. Majority districts of KP and Punjab witnessed the official price of pulses disregarded with only one exception—Masoor was sold as per official prices in 54% of Punjab’s districts.

In the meat category, beef and mutton (average quality with bone) were overpriced in 64 percent of the surveyed districts, and chicken in 39 percent of the areas. Mutton, beef, and chicken sold at Rs929, Rs449, and Rs120, respectively, above the official rates. The highest difference in the market and the official prices of mutton and beef was in Karachi South and of chicken in Ziarat.

Unlike the preceding weeks, chicken prices rose in 14 districts—five in Punjab, four in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, three in Sindh, and two in Balochistan—that recorded a two percent (Rs2) to 47 percent (Rs90) hike in rates. On the other hand, nine districts saw a four percent (Rs5) to 30 percent (Rs60) decrease in chicken’s market prices. In the remaining seven regions, the prices remained stable.

This interactive graph may be used to view the percentage of areas where official prices of essential commodities were missing.

TDEA-FAFEN generates the Weekly Price Monitor covering 15 essential kitchen items, including groceries such as wheat, pulses, oil, sugar, and perishable commodities like meat, and vegetables. It does this considering the need for an independent and regular assessment of the availability of such items. The observers obtain the official prices from the officials of district administrations, or market committees, and collect the wholesale prices through market surveys. In Punjab’s case, the government price app Qeemat Punjab is also used to get the official rates.

To download the report, click here