ISLAMABAD, September 2, 2020: Vegetables, pulses, and meat remained the most unregulated commodities in most parts of the country as markets in more than half of the districts disregarded the officially notified prices of these items.

These observations form part of the 18th Weekly Price Monitor issued by the Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN). This monitor comprises a market survey of the prices of 15 basic groceries conducted on Thursday, August 27, 2020, in 26 cities—10 each in Balochistan and Punjab, four in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and two in Sindh. FAFEN could not observe some cities due to heavy rains.

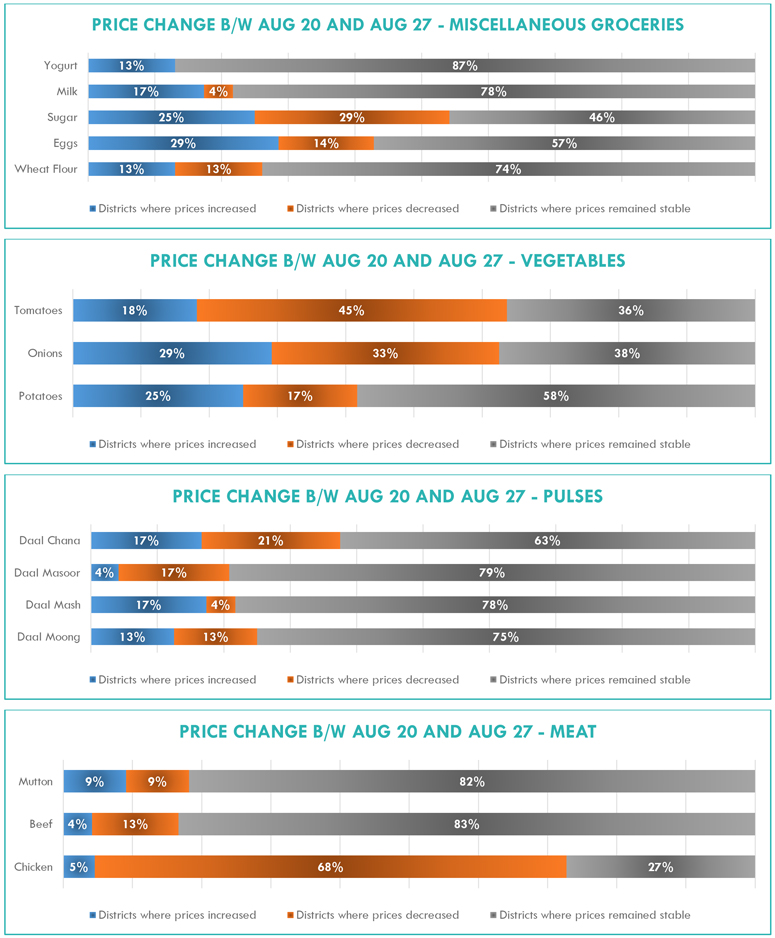

A two-week comparison of routine vegetables’ market prices, i.e., potatoes, onions, and tomatoes, showed varying patterns. Among the everyday groceries, the pulses’ prices remained mostly stable—less than a quarter of the surveyed districts, recording an increase or a decrease in the prices. Among the vegetables, around three-quarters of the areas showed a decline or stability in prices during the reporting week compared to the previous one. The meat prices also remained mostly stable except chicken, which showed a declining trend. Egg prices registered an increase in 29 percent districts, sugar in 23 percent regions, milk in 14 percent areas, and wheat flour and yogurt in 13 percent districts.

The following graphs depict the overall trend of change in prices of essential edibles:

The officially notified price lists of essential commodities were unavailable in various parts of the country during the reporting week. The official rates of 20-kilogram wheat flour bags were not available in around 35 percent of the surveyed cities. Like previous weeks, the unavailability of official wheat flour rates at shops was most significant in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh, where 75 percent and 100 percent of the districts lacked the official prices.

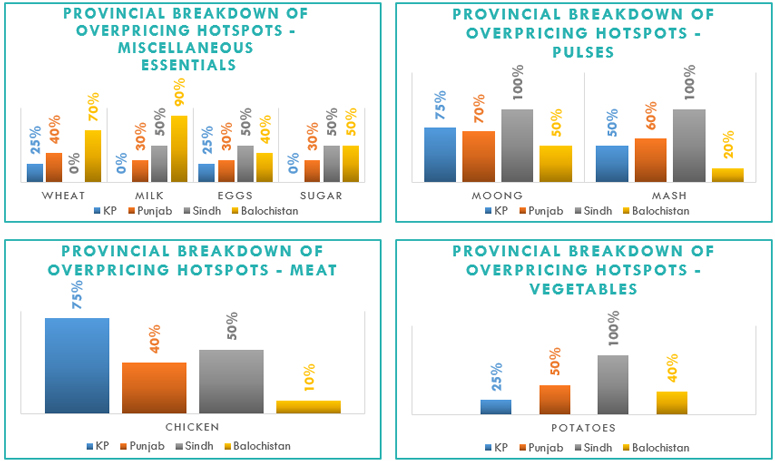

The official sugar prices were missing in more than half (58 percent) of the districts—100 percent in KP, 60 percent in Punjab, 50 percent in Sindh, and 40 percent in Balochistan. Similarly, the chicken prices were not obtainable in 70 percent of districts in Balochistan and 50 percent in Sindh. In contrast, they were available at all of the surveyed markets in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

The official rates of four pulses—moong, masoor, mash, and chana—were generally available in KP, Punjab, and Sindh. However, they were missing at several markets in Balochistan. Daal mash prices were unavailable in 50 percent of the markets while 40 percent lacked daal masoor and daal chana rates, and another 20 percent did not have daal moong prices. At the same time, milk and yogurt rates were not publicly obtainable in 23 percent and 31 percent areas.

Moreover, mutton and beef prices were missing in 15 percent and eight percent of the districts. Provincially, the beef prices were missing in 50 percent regions of Sindh, and 10 percent in Punjab. In contrast, mutton prices were unavailable in 50 percent of markets in Sindh, 25 percent in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and 10 percent each in Punjab and Balochistan. The meat prices used to be publicly accessible in all of the Balochistan markets during the previous weeks. The official price lists of regular vegetables—potatoes, onions, and tomatoes—were inaccessible in around 30 percent to 40 percent of Balochistan markets while elsewhere, they were publicly available.

The interactive graph below shows the percentage of areas where official prices of essential commodities were missing:

Besides the unavailability of officially notified prices of essential groceries, the official prices’ enforcement remained weak.

Daal moong price remained the most unregulated, with 65 percent of the markets selling it at a higher rate than its official price. Similarly, daal chana was overpriced in 50 percent markets, and daal masoor and daal mash in 46 percent markets each. Like the previous weeks, the pulses’ overpricing was most prominent in Sindh, where no market sold any of the four pulses at official prices. These four pulses went 108 to Rs184 above the Karachi South district’s official prices which reported the highest difference in wholesale prices and the official rates.

Nearly 46 percent of markets sold potatoes at higher than official prices, while 58 percent markets overpriced onions and tomatoes. The tomatoes rate went Rs60 higher than the notified price in Lasbela, while potatoes and onions were sold Rs25 and Rs30 above the announced prices in Washuk and Panjgur.

In the meat category, beef and mutton (average quality with bone) were overpriced in 62 percent and 54 percent of the surveyed districts, and chicken in 35 percent. Mutton, beef, and chicken were sold at Rs500, Rs200, and Rs64above the official rates. The highest difference in the market and the official chicken prices was in Karachi South, of mutton in Multan, and beef in Killa Abdullah.

Traders sold wheat flour and refined sugar above the official rates in 46 percent and 35 percent districts. A 20-kilogram bag of wheat flour was priced Rs400 above the official rate in Washuk, and one kilogram of refined sugar Rs36 more than the market price in Karachi South. Of the four provinces, wheat price enforcement was the weakest in Balochistan, where 70 percent of markets sold it above the officially notified rates. The sugar price enforcement was the lowest in Sindh and Balochistan, where half of the surveyed markets sold it above the official prices.

The market rates of eggs per dozen were above the officially notified prices in 35 percent districts. Simultaneously, the rates of milk and yogurt were higher than the official ones in 50 percent of the surveyed areas.

TDEA-FAFEN generates the Weekly Price Monitor covering 15 essential kitchen items, including groceries such as wheat, pulses, oil, sugar, and perishable commodities like meat, and vegetables. It does this considering the need for an independent and regular assessment of the availability of such items. The observers obtain the official prices from the officials of district administrations, or market committees, and collect the wholesale prices through market surveys. In Punjab’s case, the government price app Qeemat Punjab is also used to get the official rates.

To download the report, click here